orthofox

Well-Known Member

Planking the Gundeck: Rolling hemp and butting joints.

Mr. Allen, Master: [after seeing that the Acheron is closing in on them] My God, what can we do? He has us by the hip.

Capt. Jack Aubrey: Run like smoke and oakum.

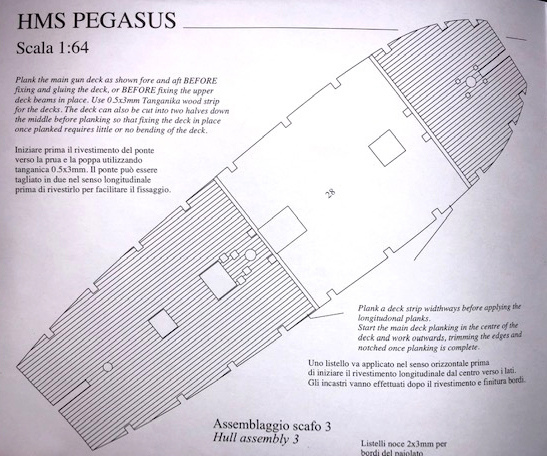

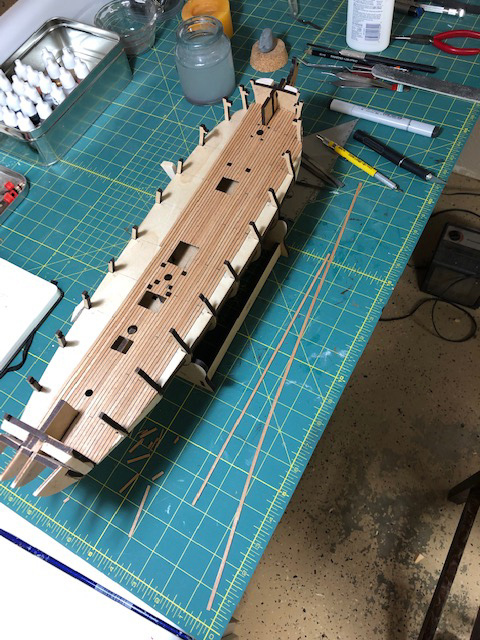

So what is oakum and why am I bringing it up here? Because we're about to plank a deck! Well, I'm about to pretend like I know how to plank a deck to be more specific. First, I have to note that I'm really straying from the directions on this part. They are vague at best. For example, the provided illustration shows the false deck to be one entire piece of plywood, not the actual split deck that the kit provides. Next, they suggest dividing the deck into thirds with transverse planks to trifurcate the deck planking. From what I've read, this would never have been done on a real ship.

Lastly, they instruct to plank the false deck before installing it which is just crazy talk, because the end result would be a deck so rigid that I don't think I'd ever be able to fit it between the frame uprights or get it to take on the gentle arc to match the 'beams' of the bulkhead frames.

So, I will be planking the entire length of the false deck in situ.

For another real world ship building lesson, I turned back to the Traditional Maritime Skills website (link) for a tutorial. Ship decks are planked with longitudinal strips of wood. But one edge of each plank has a subtle bevel cut into it which creates what is called a seam.

These seams are not full thickness.

The seams are caulked which serves two purposes. First, they make the deck water proof. But secondly, they provide tremendous structural support to the deck by inhibiting the planks from sliding back and forth on one another in a pitching sea. Thus, good caulking provides stiffness to the overall deck and a waterproof barrier to the decks below. There are many ways to caulk a wooden deck, but what would have been typical in the 18th century is to apply oakum and pitch. So what is oakum? It is a complex array of fibers made from strands of hemp, jute or other materials used for making rope (even from old ship's ropes) that is then soaked in tar or oil to make it waterproof.

If you visit the aforementioned site, you can watch shipwright and all around bad-a$$ Chris Rees caulk the deck planks.

First step, twisting the oakum into a cord.

Then using a mallet (never a hammer) and a making iron (kind of like a wedge) to seat the oakum into the seam.

Then tapping it even further in with a caulking mallet and hardening iron to firm it up.

(I want one of those. I have no idea what I'd use it for, but I want one. Anyway...)

After the seam has been caulked with oakum, it would be coated with pitch or tar, probably twice in a large ship. The excess would be scraped free from the deck.

The reason I mention all of this, is that there is very definitely a resulting striped pattern to the resulting deck planks and dark caulk that I'll want to try to replicate.

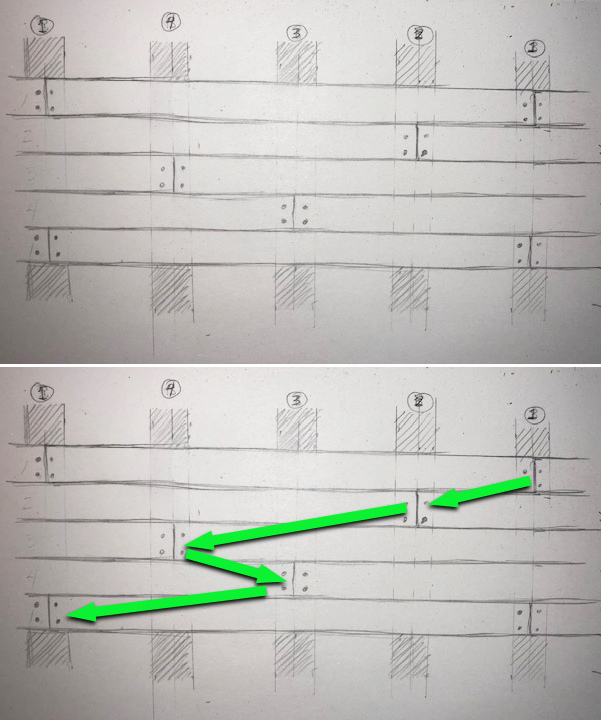

The next thing to mention is that there are various patterns of deck planking which stagger the joints to maximize the structural integrity. I couldn't find a reference that specified which pattern the Pegasus would have had, but from what I read, most ships of that time would have had either a 3 or 4 butt shifting pattern. I decided to go with the 4 butt and drew this out in my build notebook to make sure I understood it before I started.

As you can see, it's just a repeating pattern of where the butt joints fall. I used the frame bulkheads to determine where to place each joint and numbered them accordingly.

The deck planking provided in this kit is 0.5 X 3 mm tanganyika.

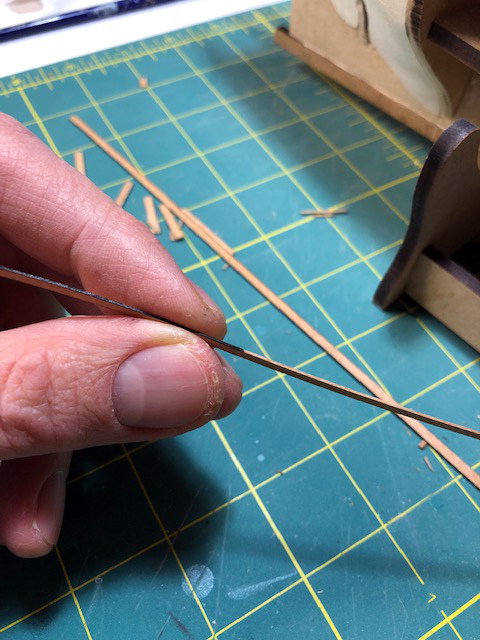

When I placed some planks next to one another I noticed they are so precisely milled, that no seam was apparent between them. Again, I wanted to highlight the presence of a black-pitched caulked seam. From various threads online I learned that many ship modelers will do this either by lying black thread between the planks or somehow marking up the plank edges with charcoal, crayon or ink. After some experimentation, I settled on marking the plank edges with the chisel tip end of a dark charcoal grey Copic marker.

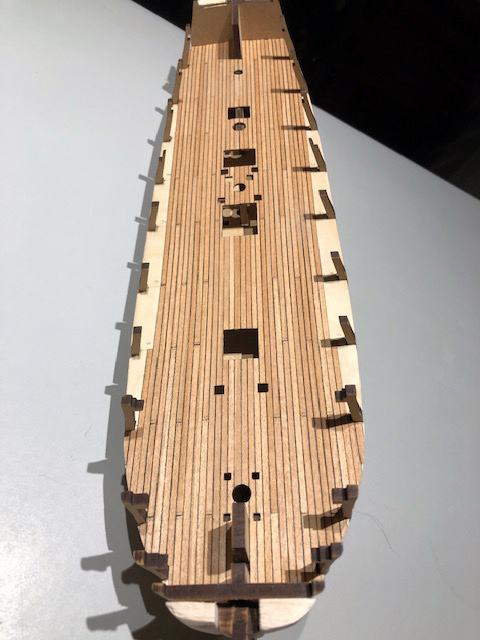

You can see the effect here between marked and unmarked.

In using this technique, i noticed that each plank has a rough-sawn side and planed side. The rough-sawn side wicked the ink from the pen more and had a tendency to bleed. So I just needed to make sure the planed side was face up.

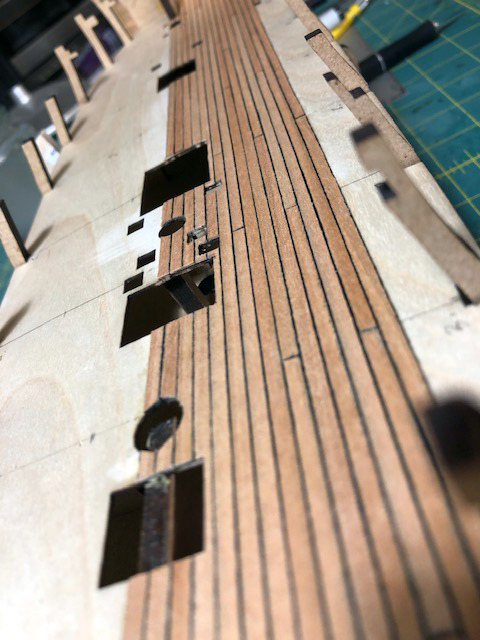

Then, the planking commenced. I had two options regarding how to start. Option 1 would be to place something called a kingplank, or single line of planks (also called a strake) right on the midline of the deck from bow to stern. This would establish the line of all subsequent planks. But because my false deck was already bifurcated by the kit designers, I decided to go with option 2: place two strakes, one either side of that bifurcation, each following that straight edge precisely. There are many holes and openings in the false deck that will accommodate various deck features, and the planking had to be cut and carved around each. From there, strake after strake was applied working from midline outward following the 4-butt shift.

I had read that deck planking can get very tedious and boring, but I found it rather meditative. BTW, my wife says I'm really weird, so take everything with a grain of salt.

I just plugged away at it for 1-2 hours a night while listening to a podcast or some music and as the end of the week approached nearly had the whole thing complete.

You will note, that entire deck is NOT complete, however. And that is because the uprights of frames #5, 6 and 7 will actually be removed down to the false deck after the gun port bulwarks are attached. Those cut members then need to be planked over. So I need to leave this segment of the deck unfinished for now. (Remember I said you have to read 5 steps ahead before you do anything...)

Lastly, I wanted to depict how the planks would have been attached to the frames. Conventionally this would have been done with something called treenails (also referred to as trunnel or trennals) which were essentially wooden pegs that may or may not have a wedge in one end to expand the treenail in place. When the end grain of a treenail got wet, it would swell and expand and they would tighten within the hole. I'm not sure the treenails would be seen at 1:64 scale, but I decided to mark some on each each frame with a 0.3mm pencil lead.

Once again, I'm going to be straying from the directions for the next step and jumping straight to the gun port / bulwarks. This will require my first exposure to needing to bend wooden elements in hot water and / or steam. I have zero experience doing this so am a bit nervous. All of this is to say there may be some major Schadenfreude potential in the forthcoming posts. Stay tuned.

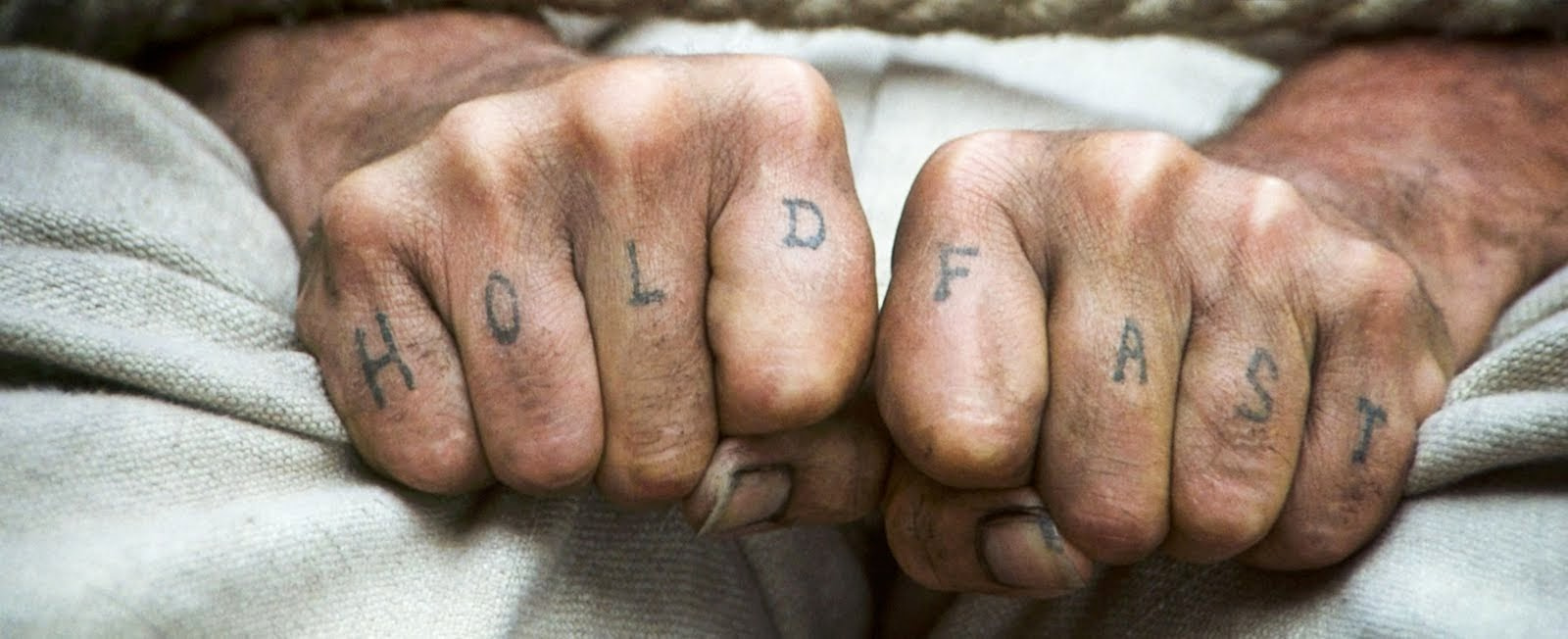

Next up: Hold Fast!

Mr. Allen, Master: [after seeing that the Acheron is closing in on them] My God, what can we do? He has us by the hip.

Capt. Jack Aubrey: Run like smoke and oakum.

So what is oakum and why am I bringing it up here? Because we're about to plank a deck! Well, I'm about to pretend like I know how to plank a deck to be more specific. First, I have to note that I'm really straying from the directions on this part. They are vague at best. For example, the provided illustration shows the false deck to be one entire piece of plywood, not the actual split deck that the kit provides. Next, they suggest dividing the deck into thirds with transverse planks to trifurcate the deck planking. From what I've read, this would never have been done on a real ship.

Lastly, they instruct to plank the false deck before installing it which is just crazy talk, because the end result would be a deck so rigid that I don't think I'd ever be able to fit it between the frame uprights or get it to take on the gentle arc to match the 'beams' of the bulkhead frames.

So, I will be planking the entire length of the false deck in situ.

For another real world ship building lesson, I turned back to the Traditional Maritime Skills website (link) for a tutorial. Ship decks are planked with longitudinal strips of wood. But one edge of each plank has a subtle bevel cut into it which creates what is called a seam.

These seams are not full thickness.

The seams are caulked which serves two purposes. First, they make the deck water proof. But secondly, they provide tremendous structural support to the deck by inhibiting the planks from sliding back and forth on one another in a pitching sea. Thus, good caulking provides stiffness to the overall deck and a waterproof barrier to the decks below. There are many ways to caulk a wooden deck, but what would have been typical in the 18th century is to apply oakum and pitch. So what is oakum? It is a complex array of fibers made from strands of hemp, jute or other materials used for making rope (even from old ship's ropes) that is then soaked in tar or oil to make it waterproof.

If you visit the aforementioned site, you can watch shipwright and all around bad-a$$ Chris Rees caulk the deck planks.

First step, twisting the oakum into a cord.

Then using a mallet (never a hammer) and a making iron (kind of like a wedge) to seat the oakum into the seam.

Then tapping it even further in with a caulking mallet and hardening iron to firm it up.

(I want one of those. I have no idea what I'd use it for, but I want one. Anyway...)

After the seam has been caulked with oakum, it would be coated with pitch or tar, probably twice in a large ship. The excess would be scraped free from the deck.

The reason I mention all of this, is that there is very definitely a resulting striped pattern to the resulting deck planks and dark caulk that I'll want to try to replicate.

The next thing to mention is that there are various patterns of deck planking which stagger the joints to maximize the structural integrity. I couldn't find a reference that specified which pattern the Pegasus would have had, but from what I read, most ships of that time would have had either a 3 or 4 butt shifting pattern. I decided to go with the 4 butt and drew this out in my build notebook to make sure I understood it before I started.

As you can see, it's just a repeating pattern of where the butt joints fall. I used the frame bulkheads to determine where to place each joint and numbered them accordingly.

The deck planking provided in this kit is 0.5 X 3 mm tanganyika.

When I placed some planks next to one another I noticed they are so precisely milled, that no seam was apparent between them. Again, I wanted to highlight the presence of a black-pitched caulked seam. From various threads online I learned that many ship modelers will do this either by lying black thread between the planks or somehow marking up the plank edges with charcoal, crayon or ink. After some experimentation, I settled on marking the plank edges with the chisel tip end of a dark charcoal grey Copic marker.

You can see the effect here between marked and unmarked.

In using this technique, i noticed that each plank has a rough-sawn side and planed side. The rough-sawn side wicked the ink from the pen more and had a tendency to bleed. So I just needed to make sure the planed side was face up.

Then, the planking commenced. I had two options regarding how to start. Option 1 would be to place something called a kingplank, or single line of planks (also called a strake) right on the midline of the deck from bow to stern. This would establish the line of all subsequent planks. But because my false deck was already bifurcated by the kit designers, I decided to go with option 2: place two strakes, one either side of that bifurcation, each following that straight edge precisely. There are many holes and openings in the false deck that will accommodate various deck features, and the planking had to be cut and carved around each. From there, strake after strake was applied working from midline outward following the 4-butt shift.

I had read that deck planking can get very tedious and boring, but I found it rather meditative. BTW, my wife says I'm really weird, so take everything with a grain of salt.

I just plugged away at it for 1-2 hours a night while listening to a podcast or some music and as the end of the week approached nearly had the whole thing complete.

You will note, that entire deck is NOT complete, however. And that is because the uprights of frames #5, 6 and 7 will actually be removed down to the false deck after the gun port bulwarks are attached. Those cut members then need to be planked over. So I need to leave this segment of the deck unfinished for now. (Remember I said you have to read 5 steps ahead before you do anything...)

Lastly, I wanted to depict how the planks would have been attached to the frames. Conventionally this would have been done with something called treenails (also referred to as trunnel or trennals) which were essentially wooden pegs that may or may not have a wedge in one end to expand the treenail in place. When the end grain of a treenail got wet, it would swell and expand and they would tighten within the hole. I'm not sure the treenails would be seen at 1:64 scale, but I decided to mark some on each each frame with a 0.3mm pencil lead.

Once again, I'm going to be straying from the directions for the next step and jumping straight to the gun port / bulwarks. This will require my first exposure to needing to bend wooden elements in hot water and / or steam. I have zero experience doing this so am a bit nervous. All of this is to say there may be some major Schadenfreude potential in the forthcoming posts. Stay tuned.

Next up: Hold Fast!

Last edited: